The Dutch city of Breda is located in the southern Brabant province. Aside from its cultural riches, a pretty well-known prison named de Koepel, or ‘the Dome’, is situated there. In the wake of the Second World War, the prison housed all Dutch war-criminals serving life sentences. Some of them had their death sentence commuted. Others simply served life. 111 Dutchmen and 63 Germans. Among them were ‘Breda’s Seven’; seven Dutch former Waffen-SS war-criminals serving life sentences.

By G.Lanting – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5313286

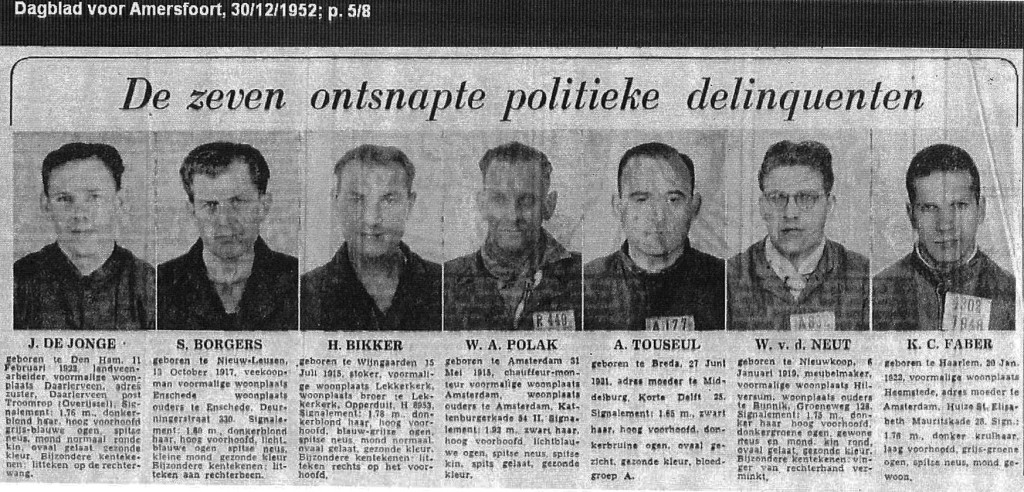

Yet seven years after the Second World War came to an end and the Dutch court sentenced these men to life, they managed to escape the prison and flee the country. This event dominated the national headlines, and there was an enormous public backlash. Not so much because of the escape itself, but because of the aftermath… Although it was known where the escapees fled and where they resided, it appeared that all of them managed to get away with it. In 2018 the Dutch National Archives released confidential ministerial letters, memos and reports regarding the escape. These provide a candid look at the subsequent diplomatic fallout.

The Escape

On December 26, 1952, Boxing Day, the prison hosted a movie night for its inmates. The 1935 black-and-white Austrian comedy Der Himmel auf Erden was played in the common room. But seven former Waffen-SS members and war-criminals serving life sentences weren’t watching the film. Herbertus Bikker, Sander Borgers, Klaas Carel Faber, Jacob de Jonge, Willem van der Neut, Willem Polak and Antoine Touseul were planning their escape. With help from sympathisers on the outside.

Letters and documents reveal these men were serving their sentences for a long list of crimes against humanity. During the Second World War, they committed murder, abuse and reprisals against unarmed civilians. They aided and abetted the deportation of Jews, some being camp-guards themselves.

As soon as the common room lights extinguished, the seven prisoners snuck to the prison’s boiler room. They pick locked the door that led them to the courtyard. One of the men worked in the boiler room and hid a ladder under piles of coal there earlier that day. Using both the ladder and a firehose, all seven managed to climb over the five-meter high outer perimeter wall, unnoticed by any guard.

Outside two cars stood at the ready, a Plymouth and Chevrolet. It appeared the men received help from outside and that this escape wasn’t a spur-of-the-moment thing. It had been thoroughly planned. After the men jumped into the cars, they drove to Germany. Within two hours, at around 10 PM that night, they crossed the border. Upon arrival in Germany, they reported themselves to the local police. Some sources indicate the local police officer that happened to be on duty that night was a former SS officer himself, instantly sharing the department’s Christmas stollen and brewing the prisoners a pot of coffee.

Meanwhile, in prison, halfway through the film, the lights suddenly turned on. Someone tipped the guards an escape had taken place, although the guards were unsure who, and how many escapees there were. After a rollcall they counted 167 prisoners: seven were missing. But it was too late, and most of the prisoners would never return to the Netherlands.

During the subsequent proceedings of German authorities against the fugitives, a German district judge, Dyckman, convicted all men… for illegally crossing the border. They were fined 10 Marks each. The fact the men only had Dutch guilders to pay the fine didn’t really matter. It appeared they quite literally escaped justice.

Backlash

Now, you’d expect the men to be extradited to the Netherlands as the German authorities found out they resided in the country. Because, well, they were Dutch citizens. Yet that wasn’t the case. Since 1943 any person of a ‘Germanic nation’ such as the Flemish or Dutchmen that joined up with the Wehrmacht or Waffen-SS automatically received German citizenship. This was thanks to the so-called Führer-Erlass, directives issued by Adolf Hitler himself.

Post-war German law prohibited extradition of its own citizens. So German courts used this argument to obstruct any way shape or form, leading to these Dutch fugitives’ extradition. In turn, all of them began new lives in Germany.

It’s fascinating to read letters from the Dutch ambassador Pim van Boetzelaer, complaining about this “ridiculous argumentation, because all these men are as Dutch as can be.” Three years after the escape, in October 1955, the German ambassador to the Hague received a firm reprimand from the Dutch government. In a letter, the government complained about the deterioration of confidence in the German rule of law. Mainly because the German courts used the Führer-Erlass as an argumentation not to extradite the men. After all, the decree was a thoroughly national-socialist decree, issued by Hitler himself. How could Germany, after all the crimes committed by the Nazi regime, uphold such an order?

Writing about the case in private letters, the Dutch Justice Minister Leendert Donker complained about it being “highly unsatisfactory and completely untenable.” He also criticised the Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs, Joseph Luns. Apparently, Luns promised to ensure that he’d reach an agreement with the Germans regarding the issue. But three years down the line there was no word about it yet.

Coded telegrams sent by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reveal a painfully obvious absence of Allied countries’ support. In one such telegram from February 1955, they write that extradition of ‘bandits’ isn’t a priority to Washington, London or Paris. They had bigger fish to fry. To be fair, due to the Cold War, there was ever-increasing tension between the Soviet Union and the Western nations. It was a priority to ensure support from West Germany, and agitating them by twisting their arm into extraditing the men could work counterproductive. Dutch interest was secondary to these massive geopolitical interests forming a block against the Soviet Union and its satellite states.

This too became painfully obvious to the Dutch government. On October 27, 1955, Minister Donker wrote that “any chance of extradition of these men is close to zero. It is a lost cause.” And Donker wasn’t too wrong. All men got away with it. Well, except for Jacob de Jonge, a former camp guard who ended up not being eligible for German citizenship. He was extradited to the Netherlands and served part of his sentence. I couldn’t for the life of me find out how long he did serve, although it is near certain he did not serve a life sentence anymore.

As for the prison itself, in the immediate aftermath of the escape, the prison, housing dozens of war criminals, increased the height of the walls and erected multiple guard towers.

Curiously enough the three men driving the cars and helping the escapees were arrested and put on trial in the Netherlands. All three were native Dutchmen from Amsterdam. It turned out they served prison sentences in the aftermath of the war for assisting the Germans during their occupation of the Netherlands.

Dutch newspapers publicised their names and their defence. The interrogation reports are included in the secret archives of the Dutch Justice Ministry. It was quite laughable: they stated they were simply driving around, looking at Dutch meadows, when they ran into the group of escaped prisoners. On a whim, they decided to give the men a ride. They supposedly didn’t know they were helping war-criminals escape. At any rate, all four were sentenced to six months imprisonment for aiding the escapees.

Herbertus Bikker, nicknamed the Hangman of Camp Ommen, ended up standing trial in Germany in 2003 – 51 years after his escape. The Germans charged him with the murder of a member of the Dutch resistance, Jan Houtman. Yet psychiatrists advised the court that Bikker wasn’t mentally capable of understanding the charges brought against him anymore. As such, the German courts decided to halt prosecuting him. Bikker was never convicted for any of his crimes, just like the others, except de Jonge.