In early 1940, the Second World War truly began taking shape in the European theatre. On April 9, 1940, Denmark capitulated to invading German forces. One month later, the Phoney War ended as Germany successfully launched its invasion of Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and France.

However, on that fateful day, May 10 1940, Germany wasn’t the only country to cross nearby borders and invade other countries. Because Great Britain did just that, on that same morning the Phoney War ended. They invaded the tiny island of Iceland, situated in the North Atlantic Ocean.

Preparations

Now, the invasion of Iceland was curious for multiple reasons. We’ll have to briefly gloss over its recent history to understand why – but there was one main reason: the island did not have an army, nor did it have a navy. In fact, Iceland was very dependent on Denmark for its defences. Sure, Denmark recognised their former colony as a sovereign state since December 1918, but the island still entirely relied on Denmark in terms of military power.

The island itself housed a little under 360.000 civilians. With an area a bit over 100 square kilometres, making it the most sparsely populated country in Europe.

Although Iceland is sparsely populated, it is exceptional for not having a military even among small countries. For example, Luxembourg has a population just a tad larger at 626.000 inhabitants but has a fully equipped and trained infantry battalion. Well, the census of December 2018 reveals they employ 414 soldiers in active service. Perhaps not enough to win any type of war, considering its neighbours, but still. Even the Vatican, with just over 800 inhabitants, has its own personal halberd-wielding army.

So why didn’t Iceland have an army? There certainly is enough lore talking of the wars and battles among the Vikings, the civil war between clans fighting over control, and the eventual development of Iceland’s rulers as vassals of Kings of Norway and later Denmark. In the 16th century, the island was still a Danish colony. The Danish king didn’t expect other colonial powers to wage war over Iceland’s territory. Because deploying soldiers at a remote base such as that did get costly, he decided to completely disarm the northern colony.

And frankly, disarming the entire island didn’t lead to that many problems. Most of Iceland’s modern military history can be characterised by pacifism. Denmark took care of its protection, even after the aforementioned Act of Union of December 1918, wherein Denmark recognised the island as a fully sovereign state. Because of its remote location there simply weren’t any proper threats to the island.

Although there were financial impacts, the island did not experience any bloodshed during the First World War. Yet during the interbellum already the island was seen as an ideal strategic military base for expeditions and operations in the northern seas—both to the Germans and British. After the successful invasion of Poland and the subsequent overpowering of the neutral countries of Denmark and Norway in April, the British began to realise they may be the only ones left in Europe to fight the rapidly advancing Germans. Rapid action was required to do so.

The very same day news reached England of Germany’s invasion of Denmark and Norway, they sent out telegrams to several countries, pleading to declare war on Germany. Among these countries was tiny, neutral Iceland. The British proposed Iceland an alliance that would guarantee the countries’ neutrality. In turn, the Royal Navy and army wanted access to all airfields and harbours. Hermann Jónasson, Iceland’s prime minister, rejected the offer, disregarding that he knew Iceland didn’t have an army to withstand an invasion from whichever side.

Invasion of Iceland

Upon receiving news of the rejection, British prime minister Winston Churchill was livid. After what happened with Norway and Denmark, there was no way he could allow Iceland to fall into German hands uncontested. Nearly a month later, on May 6, the British began planning so-called Operation Fork, the invasion of Iceland.

The 2nd Marine Squadron under the command of Colonel Robert Sturges was the force chosen for this invasion. 746 British marines participated. Many of these marines hadn’t yet completed their training, and all of them were poorly equipped. The lack of training can be understood because the squadron had only existed for just one month. Many recruits were still in basic training, rarely having shot a rifle if they even had a rifle at all. Also, all maps of Iceland that were available to the army and Royal Navy were outdated. Not to mention the fact there was not a single marine able to speak Icelandic.

So these logistical parts of the mission weren’t exactly… up to standards. It shouldn’t be a surprise the initial stages of the mission were an embarrassing but in hindsight, pretty amusing failure. To begin with, the invasion had to take place on May 9 but was postponed to the following day because the marines ran late to reach their point of departure. Because of the time constraints, they left a lot of ammunition and supplies in the British harbour.

The vessels brining the marines to Iceland were HMS Berwick and HMS Glasgow. Yet, these vessels did not have enough capacity to house all marines comfortably, and during the transit, many marines became seasick due to their inexperience. According to eyewitness accounts, several marines that were fortunate enough not to get seasick decided to use the journey for some rifle practice.

So on the night of May 9 to 10, two stacked vessels sailed towards Iceland. HMS Berwick decided to launch a Supermarine Walrus reconnaissance aircraft. The thing is, it was not even 2 AM by this point – dead quiet. Not to mention Iceland didn’t have an airforce. As such, the noise of the plane’s motors woke up the entire island.

It took a few more hours for the British to finally sail into the ports of Reykjavik. When they finally ‘invaded’ the country, a delegation of 76 policemen stood at the ready, waiting for them. When the Icelandic policemen realised they were dealing with a considerable invasion force, they understood they stood no chance. In the harbour, the British consul was waiting with the police officers. When he requested them to push back the ever-growing crowd so the soldiers could more easily disembark the boat, the policemen willingly obliged.

Once disembarked, the marines began putting up flyers in Icelandic, containing several grammatical errors. The flyers informed the local populations of the occupation. During those initial hours, the British didn’t face any resistance and were able to disable all communication networks on the island. They occupied the harbour and other strategic positions in town.

They preemptively arrested any German citizen they came across. The German Consul, Werner Gerlach, had been aware of the impending invasion thanks to the Supermarine Walrus reconnaissance aircraft circling over the city during night time. He spent the entire morning burning sensitive documents. When marines came by, Gerlach pointed out they had just invaded a neutral country. The argument was swiftly parried by stating Denmark and Norway had been just as neutral.

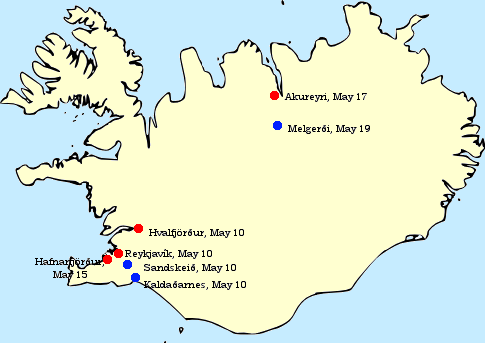

Once Reykjavik was occupied, the marines began building an air defence system within the capital, and several units went on their way to secure the rest of the island. By claiming local transportation means, troops moved north to capture cities such as Hvalfjörour, only to push forward during the next several days and capture the northern town of Akureyri.

Taking control of the northern part of the island was crucial to prevent any German naval counteroffensive from happening. Subsequently, the cities of Kaldaoarnes, Sandskeioi and Akranes were taken to avoid an aerial assault with Fallschirmjäger from overpowering the British forces. Those same Fallschirmjäger had wreaked havoc behind Allied lines. For example, Eben-Emael was once deemed Belgium’s impenetrable fortress, but quickly overtaken by a German paratrooper force.

So how did Iceland’s government and population respond to this sudden act of aggression from the British? Well, on the evening of May 10, Iceland’s government formally protested. They noted how Britain violated Iceland’s neutrality and sovereignty. They realised they weren’t in an actual position to resist, though. As this article from a Texan newspaper shows, the country had neither army nor navy. They demanded the British compensate them for all damages led during the invasion, to which the British government agreed.

The British government also agreed they would withdraw all forces once the “conclusion of all hostilities” was reached. To their allies, they communicated they took “protective custody” of the tiny island. It was quite a bloodless invasion. However, there was one casualty… albeit not on the island. As the marines were sailing to Iceland preceding the invasion, one of the men decided to take his own life. Details about the why and how are entirely unclear, but it is noted that the only victim of Operation Fork was just that poor marine.

As for the subsequent events, the initial invasion force wasn’t at strength to safeguard the island against a potential German counterattack. Seven days after the first boots on the ground, 4000 British soldiers relieved the marines. Over time the British military increased this to 25.000 soldiers until the Americans relieved all British troops one year later.

In that sense, the Second World War in Iceland was pretty uneventful. Up until the Germans’ surrender in 1945, the Americans simply held the island to prevent any lost German weather units from sailing onshore and taking over control. After all, there were quite a few German weather stations nearby in the arctic.

Iceland’s final “war”

But with Germany’s surrender in 1945, the American presence in Iceland didn’t end. They never left. During the subsequent ‘Cold War’, Iceland only increased in strategic importance. The island literally lay on the Soviet-navy sailing route from the ice-free harbours of Murmansk to the Atlantic Ocean. In 1946 the Icelandic government granted the United States the right to establish the Keflavík airbase, located approximately 40km north of the capital Reykjavík. Having Americans stationed there didn’t prevent Iceland from getting in fights with its Allied neighbours.

Now, already before and after the Second World War, most of Iceland’s economy depended on its fishermen. When the availability of fish declined, it was a direct threat to the Icelandic economy. It is the primary reason why Iceland vehemently opposed over-fishing by other nations in or nearby their waters.

This self-preserving ‘hostile’ stance led to four maritime conflicts, which became known as the Cod Wars. In 1952 Iceland expanded its fishery limits from 3 to 5 nautical miles, repeating this step in 1958, 1972. In 1975 they reached their limit of 200 nautical miles. Due to Britain, in return, declaring a similar zone around its own waters and other nations following suit, the 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone has been the international standard under the United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Sea since 1982.

These expansions of Iceland’s fishery limits led to multiple altercations with mainly Britain and West-German governments. Icelandic coastal guards chased away foreign fishing ships, cutting their nets and even ramming the vessels if they reached them. If not, the Icelandic Coast Guard would shoot at the fleeing ships. Because Britain obviously couldn’t accept this, battleships began escorting the British fishing trawlers.

The Cod War reached one of its curious climaxes when in 1958, a British and Icelandic fishing boat captain got in an altercation on the sea. They used megaphones to shout bible verses, condemning each other. According to journalists present on one of the vessels, the Icelandic captain won the battle of words.

The Cod Wars came to an end in 1976 when the European countries recognised Iceland’s 200 nautical miles exclusive economic zone.

I’ve briefly mentioned German weather stations in the arctic. One unit was under the command of Wilhelm Dege, who held out for quite a while on Svalbard. After the Second World War came to an end, the Germans forgot Wilhelm Dege and his unit. After the end of the war, with Europe in turmoil, it took months before someone finally rescued them. They became the last German Wehrmacht unit to surrender, and I’ve made a video about their story.